solsa

Command-line Static Analyzer Tool for Solidity Smart Contracts

Abstract

As blockchain-based technologies like cryptocurrencies, decentralised finance and non-fungible tokens (NFTs) grow in popularity, so does the demand for Solidity developers for smart contract development. One often overlooked aspect of smart contracts is gas usage, which refers to the computational cost required to execute smart contracts on the Ethereum blockchain. Reducing gas usage is crucial for cost efficiency, network scalability, and minimising the environmental impact of blockchain applications and due to the unique complexities of Solidity and smart contract programming, many developers may struggle or aren’t bothered or aware to optimise their smart contracts manually.

This is my solution to the problem, Solsa, an open-source static analysis tool written in Go, designed to automatically refactor gas-inefficient Solidity smart contracts, making them more efficient without requiring in-depth knowledge of the three gas-inefficient patterns Solsa focuses on identifying and refactoring. In testing, Solsa manages to reduce gas usage by up to 9% on around 500 real-world Solidity smart contracts, with an average refactoring time of around 5ms. With over 90% code coverage and an A+ rating from GoReportCard, Solsa is well structured, tested and effective tool for helping developers reduce gas usage. Additonally as a point of comparison, Solsa outperforms current Large Language Models (LLMs), by overcoming their limitations on file size and consistency and accuracy of following instructional prompts and overall providing significant improvements in gas efficiency for Ethereum-based smart contracts.

Optimisations

Below are the gas-inefficient patterns that solsa identifies and refactors.

Calldata Optimisation

In Solidity, memory and calldata are different types of data locations used to store variables and data. They determine how data is stored, accessed, and how much gas is consumed. Memory is the default location (although can be explicitly specified), it is a temporary, mutable (can read and write) and more expensive in gas compared to calldata. Calldata is immutable, read-only and reserved for external function’s input parameters (variables on the blockchain). If the external parameter doesn’t get modified then gas can be saved by storing the parameter in calldata instead of being copied to memory. Pure functions don’t allow on-chain variables to be modified so any parameters should be stored in calldata to save gas.

Unoptimised Contract

// SPDX-License-Identifier: GPL-3.0

pragma solidity ^0.8.0;

contract NoCalldataUsage {

// No modification of `numbers` so can optimise into calldata

function NotPureNotModFunc(uint256[] numbers) external returns (uint256) {

uint256 sum = 0;

for (uint256 i = 0; i < numbers.length; ++i) {

sum += numbers[i];

}

return sum;

}

function NotPure_ModFunc(uint256[] numbers) external returns (uint256) {

uint256 sum = 0;

for (uint256 i = 0; i < numbers.length; ++i) {

sum += numbers[i];

numbers[i] = 0; // Can't be optimised due to this assignment

}

return sum;

}

// Pure function should be optimised

function PureNoModFunc(uint256[] numbers) external pure returns (uint256) {

uint256 sum = 0;

for (uint256 i = 0; i < numbers.length; ++i) {

sum += numbers[i];

}

return sum;

}

}Optimised Contract

// SPDX-License-Identifier: GPL-3.0

pragma solidity ^0.8.0;

contract NoCalldataUsage {

// Has been optimised as external parameter doesn't get modified

function NotPure_NotModFunc(uint256[] calldata numbers) external returns (uint256) {

uint256 sum = 0;

for (uint256 i = 0; i < numbers.length; ++i) {

sum += numbers[i];

}

return sum;

}

// Can't be optimised due to external parameter gets modified

function NotPure_ModFunc(uint256[] numbers) external returns (uint256) {

uint256 sum = 0;

for (uint256 i = 0; i < numbers.length; ++i) {

sum += numbers[i];

numbers[i] = 0;

}

return sum;

}

// Pure functions can't modify external variables so all parameters should be in calldata

function PureNo_ModFunc(uint256[] calldata numbers) external pure returns (uint256) {

uint256 sum = 0;

for (uint256 i = 0; i < numbers.length; ++i) {

sum += numbers[i];

}

return sum;

}

}State Varaible Optmisation

What is the optimisation?

This optimisation involves arraging state variables to minimize storage cost and therefore reducing gas usage. In Solidity, each storage slot is 256 bits (32 bytes) so by using a bin-packing algorithm, we can sort each state variable into the smallest number of storage slots, reducing the number of gas usage which is especially important for contracts with a large number of state variables.

Unoptimised Contract

// SPDX-License-Identifier: GPL-3.0

pragma solidity ^0.8.0;

contract BasicStorage {

uint128 public id; // 128 bits (slot 1)

address public addr; // 160 bits (slot 2)

uint256 public balance; // 256 bits (slot 3)

string public favouritePet; // 256 bits (slot 4)

bool public isActive; // 8 bits (slot 5)

}Optimised Contract

// SPDX-License-Identifier: GPL-3.0

pragma solidity ^0.8.0;

contract BasicStorage {

uint256 public balance; // 256 bits (slot 1)

string public favouritePet; // 256 bits (slot 2)

address public addr; // 160 bits (slot 3)

bool public isActive; // 8 bits (slot 3)

uint128 public id; // 128 bits (slot 4)

}Struct Varaible Optmisation

What is the optimisation?

This optimisation involves arraging struct variables to minimize storage cost and therefore reducing gas usage. In Solidity, each storage slot is 256 bits (32 bytes) so by using a bin-packing algorithm, we can sort each struct variable into the smallest number of storage slots, reducing the number of gas usage which is especially important for contracts with a large number of struct variables.

Unoptimised Contract

// SPDX-License-Identifier: GPL-3.0

pragma solidity ^0.8.0;

contract EmployeeInfo {

struct Employee {

uint256 id; // 256 bits (slot 1)

uint32 salary; // 32 bits (slot 2)

uint256 age; // 256 bits (slot 3)

bool isActive; // 8 bits (slot 4)

address addr; // 160 bits (slot 4)

string role; // 256 bits (slot 5)

uint16 department; // 16 bits (slot 6)

}

}Optimised Contract

// SPDX-License-Identifier: GPL-3.0

pragma solidity ^0.8.0;

contract EmployeeInfo {

struct Employee {

uint256 id; // 256 bits (slot 1)

uint256 age; // 256 bits (slot 2)

string role; // 256 bits (slot 3)

address addr; // 160 bits (slot 4)

uint32 salary; // 32 bits (slot 4)

uint16 department; // 16 bits (slot 4)

bool isActive; // 8 bits (slot 4)

}

}GoReportCard

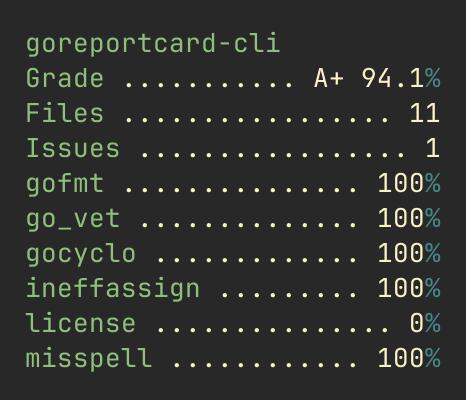

GoReportCard is a web application that generates a report on the quality of an open source Go project. It uses a variety of highly-regarded tools to give a rating/grade to your Go project including gocyclo for ensuring low cyclomatic complexity, govet for common issues like deadcode, unsafe pointers and boolean redundancies, and golint for following best practice styling guides and more.

Although GoReportCard is primarily a web app hosted at here, in the Github repository, a CLI version is also included for local and private repositories.

Above shows the results of GoReportCard analysis of the Solsa project which scores an overall A+ for the project, the only issue found was in it’s license evaluation which fails due to not having a LICENSE file in the repo. Getting A+ shows my project has passed a trusted and comprehensive quality check based on factors such as readability, maintainability, test coverage, and follows best practices in Go.

Above shows the results of GoReportCard analysis of the Solsa project which scores an overall A+ for the project, the only issue found was in it’s license evaluation which fails due to not having a LICENSE file in the repo. Getting A+ shows my project has passed a trusted and comprehensive quality check based on factors such as readability, maintainability, test coverage, and follows best practices in Go.

Solsa Performance

To evaluate the performance of Solsa and compare against the LLM, the dataset I’ll be using is solidity-blockchains-dataset (Shuttleworth, 2025), which is a Github repository containing a large collection of real-world solidity contracts that are deployed to the Ethereum network. Using the same contracts between methods will allow for an fair comparison. The contracts in the dataset contain a range of applications and uses, from cryptocurrencies, decentralised voting systems and NFTs with a range of contract sizes as small as 6 lines of code to 6355 lines of code.

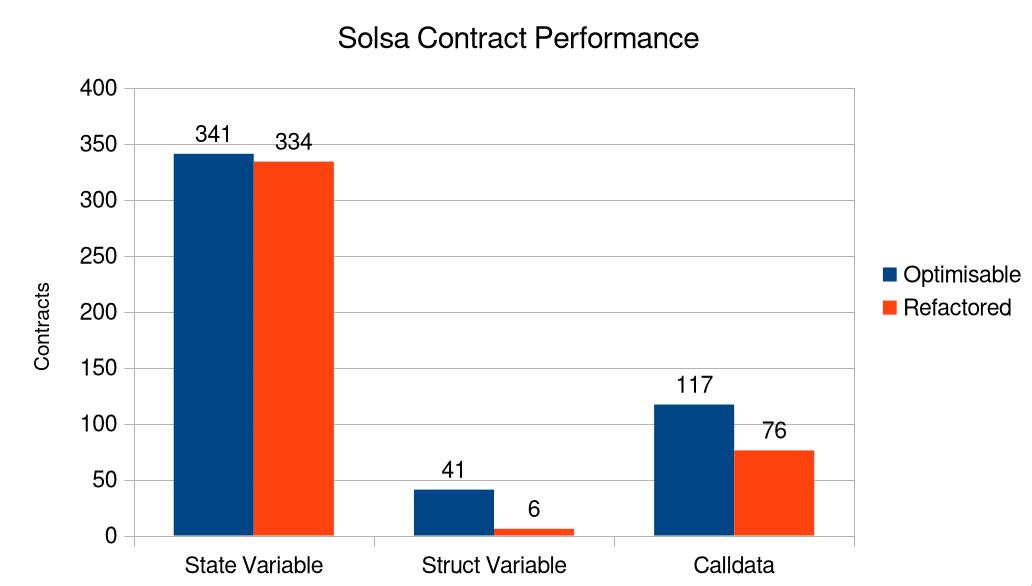

Above shows Solsa’s performance tested on 3182 available Solidity smart contracts from the solidity-blockchains-dataset (SBD), identifying a total of 499 gas-inefficient patterns and successfully refactored 416 of the patterns identified. The blue represents the gas-inefficient contracts Solsa identified as being optimisable with the orange being the number of contracts that Solsa could verifiably refactor. This distinction between verified and unverified refactoring is due to the Go module used to convert the modified AST back to source code (a fork of Solgo from 4.2.3) as it would fail on some contracts (I believe) due to not covering the full scope of the Solidity language and was unfortunantely out of scope for the project to fix. I believe the refactorings still occurred however without manually checking, it was unfeasible to verify if the contracts had been refactored sucessfully.

Above shows Solsa’s performance tested on 3182 available Solidity smart contracts from the solidity-blockchains-dataset (SBD), identifying a total of 499 gas-inefficient patterns and successfully refactored 416 of the patterns identified. The blue represents the gas-inefficient contracts Solsa identified as being optimisable with the orange being the number of contracts that Solsa could verifiably refactor. This distinction between verified and unverified refactoring is due to the Go module used to convert the modified AST back to source code (a fork of Solgo from 4.2.3) as it would fail on some contracts (I believe) due to not covering the full scope of the Solidity language and was unfortunantely out of scope for the project to fix. I believe the refactorings still occurred however without manually checking, it was unfeasible to verify if the contracts had been refactored sucessfully.